Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun is one of the best-known and most often-studied American plays of the last 60 years, but many people mistakenly assume it is an integrationist polemic. That’s perfectly understandable. The youthful playwright endured anti-black rage and violence when her family moved into a white neighborhood. But the Younger family’s encounter with the white Neighborhood Improvement Society is one episode among many.

In this Syracuse Stage production (running through March 11), Raisin feels more like a compelling family drama that justifies comparison with Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which opened a few years earlier.

Director Timothy Douglas, a Syracuse Stage favorite (A Lesson Before Dying), describes Raisin as a “touchstone” of his career, a work he has contemplated for decades. Some lines here are read differently from the way we remember them. The comic neighbor Mrs. Johnson has been deleted, and other characters are conceived differently.

In this co-production with Indiana Repertory Theatre of Indianapolis, many funds have been expended to make poverty look more authentic. Tony Cisek’s scenic design features worn period appliances and furniture but no walls. Dialogue implies the Youngers’ Southside Chicago apartment is cramped. Youthful Travis (Robert “RJ” Murphy) must sleep on a couch, but we’re surrounded by wide-open spaces.

Beyond what would be the walls are wooden staircases, perhaps evocative of earlier tenements. All stairs lead up. Overhead, unusual for any set, is the shabby ceiling, with plaster falling off the latticework.

A $10,000 inheritance sets the play in motion. The father of the family, never seen, has recently died, and his insurance benefits his widow Lena (Kim Staunton). Her son Walter Lee (Chiké Johnson), a struggling chauffeur who goes to work in a spiffy, semi-military uniform, sees the promised cash as his ticket out of deprivation. He’d like to invest in a liquor store with two pals named Bobo (local actor Donovan Stanfield) and Willie. Hansberry has chosen names that do not sound like promising entrepreneurs.

The principal tension is between the prudent Lena, still held back by the oppression of early 20th-century America, and Walter, who as an urban northerner is reminded each day of what affluence and freedom his blackness deprived him of. Lena has religious objections to alcohol and does not want to live off its profits. She really wants to use the money as a down payment on a house and the best deal around is in a now white neighborhood, which could mean trouble. Walter feels that being in business with two black pals would take him out from the stifling thumb of the white man.

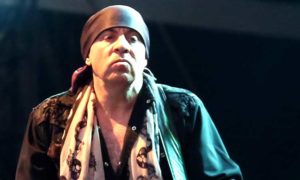

Both Staunton and Johnson are excellent at demanding tasks. Staunton has to make Lena intelligent and careful rather than weak and timid. But Johnson’s Walter supports the thematic center of the whole. The title A Raisin in the Sun comes from the Langston Hughes poem everyone knows: “the dream deferred.” Walter is the principal dreamer and he is constantly thwarted, including by his wife, Ruth (Dorcas Sowunmi), who tires of listening to his plans and aspirations and tells him to eat his eggs.

Although A Raisin in the Sun opened in 1959 when the playwright was 29, its dramaturgy feels much earlier, like the theater of Clifford Odets or Lillian Hellman. Speeches run longer than one hears in conversation, and the entire production is three hours with intermission.

All of which makes Chiké Johnson’s Walter more of an accomplishment. He’s an angry black man, one of the first ever heard on the American stage. His is the kind of voice Barack Obama eschewed, and that white America defensively tunes out. Johnson and director Douglas find nuance, self-awareness and irony in Walter’s speeches. Even in a play 59 years old, they are compelling and fresh.

In this family drama there are other voices to be heard. Walter’s sister Beneatha (Stori Ayers) has a way of drawing attention to her, often with a comic edge. She aspires to be a doctor and other paths out of Chicago’s South Side. Whereas other Beneathas have charmed with leading-lady good looks (Diana Sands played her in the 1961 movie adaptation), Ayers is imposing and bombastic. She’s a force of nature that never has to cede a scene to Walter’s anguish and anger.

In her subplot Beneatha must choose a black identity for the coming generation. On one hand there’s the fully assimilated black man George Murchison (Jordan Bellow), who sneers at Walter’s lack of education and ready cash. Not an approach to win Beneatha’s heart, in any case. Although actor Bellow has splendid professional credits, including several in Shakespeare, he is also conspicuously paler and taller than anyone else in the household. Elsewhere Murchison has been able to make a stronger pitch for abandoning Negritude. In the 1961 movie he was played by the sexy and fairly dark Lou Gossett Jr., later a leading man.

Similarly, the character who argues for finding one’s self in Africa, Joseph Asagai (Elisha Lawson), might have offered exotic romance. Lawson delivers an excellent African accent, but he’s a character player who is nearly blotted out by Ayers’ dominating presence as the towering Beneatha.

Perfectly hitting the mark in casting is soft-spoken Paul Tavianini as the seeming milquetoast from the Neighborhood Improvement Association. He offers to buy the house Lena craves, thus quelling the anxieties of the current nearby residents — and deferring her dream. His hypocrisy screams, but his words are delivered in a soft-spoken, unthreatening manner.

There’s nothing dry about this Raisin. It’s still packed with juice.

Photos taken by Michael Davis: