Ideas may buffet us or spur us, but only flesh-and-blood persons occupy space. Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (through Oct. 28 at Central New York Playhouse) and William H. Hoffman’s As Is (through Oct. 27 at Rarely Done Productions) are not often discussed together but turn out to have much in common.

Both are infused with ideological, political struggle, but both are ultimately human dramas. Both embrace a defined point of view but are anything but propaganda. In both the individual stands against predatory fate.

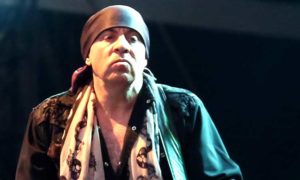

Jason Timothy and Joshua Kimball in Rarely Done’s As Is. CJ Young photo

As Is, which opened in 1985, is one of the first great AIDS dramas. It appeared about the same time as Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, but is far less bracing, often taking a disarming and unpredictable tone. Director Dan Tursi took a role in the last local production, during the 1990 Summerfest, and brings a personal commitment to the project that is discernible in every speech.

Dramaturgically, Hoffman harkens back to an earlier time, of Group Theater, so that every player speaks of his/her own first perception of AIDS before the action begins, which reminds us that many were not yet born in 1981 when the plague first appeared. Paradoxically, this tends to erase the 32 years since the play’s opening and bring it closer to us.

At their entrance, there is little to suggest that sweet-tempered Saul (Jason Timothy) and abrasive Rich (Joshua Kimball) should ever have been lovers at all. Indeed, they have already split. Rich, a poet and writer, puffed up with vanity in his muscle shirt, has fallen for the younger, sexier, but vapid Chet (Jonathan Fleischman). Saul and Rich are squabbling over household property in an early scene, in which Rich is gratuitously cruel and even anti-Semitic.

Yet it is Rich who contracts AIDS, and after a period of denial, loses his job and is shunned by his family. That’s when the discarded lover Saul comes back to Rich’s side, a love that overrides abuse and dismissal.

Thus far this may not sound political, but the actors’ pre-curtain testimonies actually set the tone. Some lamented that loud, ignorant people despised AIDS victims, a fitting punishment for gay “lifestyle,” specifically that gay relationships were promiscuous, exploitive and fleeting. Saul’s devotion refutes that.

But at the same time, As Is does not dismiss the gay embrace of risky behaviors. Rich cries out, “Oh God, I love sleaze: the whining self-pity of a leather bar in the spring, getting raped on a tombstone in Marrakesh.”

Kimball, previously seen as a slimy Scientologist in The Tomkat Project, and Timothy, best-known for musicals like Beauty and the Beast, are both in top form, with splendid support from Dorothy Lennon, Bob Fullenbaum and Heather McNeil.

Turning to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, one of the greatest of American courtroom dramas, most of us enter this much-studied masterwork knowing important details. Yes, Miller took a few liberties with characters’ ages, but a high percentage of the dialogue comes from the well-documented Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

Knowing that The Crucible opened in 1953, we can never forget that the implied offstage drama is the McCarthyite Red Scare, then raging. Yet one of the most distressing moments comes when good farmer John Proctor (Ben Sills) must confess his adultery before his sainted wife Elizabeth (Korrie Taylor), an episode Miller drew from his own life.

The unseen star of The Crucible is director Shannon Tompkins, mostly known as a choreographer and director of musicals. She banishes most of the ponderousness that has bogged down other local productions and inserts expressive movement in scenes in place of choral moaning.

Tompkins’ esteem in local theater has allowed her to line up many apt performers, starting with the affecting Ben Sills as the perceptive and sentient John Proctor, a sane man in a mad world. Almost like a time-traveler from the present, he sees on our behalf how the old, non-white, or excluded members of the community are the ones most easily accused of groundless crimes. He can never take a superior tone toward the misguided and so must futilely make a stand for sanity and the truth. The key role of Rev. John Hale (Abel Searor), the visiting witchcraft authority who has his doubts about it all, reminds Proctor that he’s not nuts.

Other fine performances include Korrie Taylor as Proctor’s vulnerable wife, John Brackett as the bullheaded cleric Reverend Parris, and Lauren Koss as the guileless Mary Warren. Simon Moody, with the most incisive chops in community theater, impressively delivers as accusing Deputy Governor Danforth.

Prudent casting choices also extend to the heedless town girls, whose lies start the witchcraft craze: Mia DiGironimo as the insinuating Abigail Williams, along with Alexandra Dubaniewicz (Betty Parris), Samantha Burton (Susanna Walcott) and Payton Vanboden (Mercy Lewis). Their faux madness helps to set this play’s courtroom scene on fire.

[fbcomments url="" width="100%" count="on"]