Carmelo Anthony and a Hasidic Jew walk into an elevator. This is not a joke. We are in the lobby of the Jack Resnick & Sons-owned offices at 199 Water St. in Manhattan’s Financial District, and this elevator is going up.

Minutes later, on the 19th floor, Anthony is standing at the spot foreign exchange desk of BGC Partners, a voice and electronic brokerage, holding a landline to his ear, conducting financial transactions.

“Ninety-two bid, 10 euros,” the six-time All-Star says into the phone. “We’re working on it.”

Looking Wall Street-sharp in a tailored suit and slim tie, Anthony is surrounded by a small flock of licensed brokers. It’s like some sort of bizarro fantasy camp, in which the NBA player gets to live out his dream of becoming a foreign currency trader. Except it’s not.

Along with a red carpet’s worth of other celebs, Anthony is in the FiDi this morning to participate in the ninth annual Charity Day, a high-profile event hosted by BGC and its former parent company, Cantor Fitzgerald, in commemoration of 9/11. One shouldn’t be surprised to find the Knicks star forward on the charity circuit — Anthony lands frequent headlines for his foundation’s philanthropic efforts — yet there is a semi-circus atmosphere at BGC, as brokers reveal themselves as dressed-up fanboys around the NBA’s scoring champ in 2012-13 and the No. 2 scorer this season, who is still waiting to seal this damn deal.

When confirmation finally comes, the FX desk erupts with high fives and backslaps. Someone shouts, “Melo’s chucking paper!” From the other end of the phone line, a voice says, “Melo, thanks, brother. Appreciate the price.” But Anthony has already dropped the receiver, now mugging for iPhone photos with one broker-fan after the next, while others try to woo him to their workstations.

“Melo! Melo!”

“Over here!”

“Melo!”

Cameras flash. A boom mic flutters overhead. Nearby, there is a tray of sandwiches. No one touches the sandwiches.

“Welcome to our zoo,” Asani Swann sighs, as we shuffle to keep up with the mayhem.

Anthony’s chief handler and the director of operations for Melo Enterprises Inc., Swann has been with the man known as Melo since his days in Denver. She is used to such scenes. “It’s weird,” she says, trailing Anthony, 29, down an internal flight of stairs. “I spend so much time with him. He’s just a normal person. He’s like a little brother.” Swann pauses. “Actually, he’s kind of gross.”

Gross or not, there is little doubt that Anthony is the biggest star in NYC’s increasingly crowded basketball universe, which perhaps explains why he draws so much attention at BGC, even when we enter a new trading room on the 18th floor. There are more celebrities here — Regis Philbin is being escorted from desk to desk, his voice booming, “Close this deal immediately!” Diddy is being Diddy, in sunglasses and a shiny suit — but the scoring champ is a magnet. With him, civilians seem to feel particularly entitled to having a word. For his part, Anthony is attentive, not rude in any way. But he also knows how to cut off each interaction, how to move on without glancing back. Yes, he looked you in the eye. No, there wasn’t a connection.

But maybe there is a way to get under the superstar’s skin. When he’s not looking, someone grabs Anthony’s suit sleeve, feeling the fabric.

“Hey!” he says, pulling away.

“What? It’s nice,” smirks Jason Kidd, the all-time great point guard who played on the Knicks in 2012-13, serving as a team leader and personal mentor to Anthony.

It is possible that the teacher-turned-rival — in June, Kidd was named the Brooklyn Nets’ head coach — is trying to play mind games with his former pupil. But Anthony smiles, unruffled. “I got one for you,” he says.

Indeed, Anthony seems to understand that everyone wants something from him this morning, be it a suit, an autograph or a prediction for the coming season. When it’s time to leave (at 11 a.m., Anthony is past due at the Knicks’ Westchester training facility), even the guys manning a cupcake station by the elevator bank have a request: Will he take a picture with them? Holding a cupcake?

Anthony grins, not wanting to say no, because he can’t say no. Saying no would make him an asshole, and he can’t be the asshole. “We have to be,” Swann says, referring to herself and Anthony’s publicist Jill, perhaps sensing something less than kosher about these elevator-bank confections. Just as one of the cupcake guys’ camera phones is coming into focus, Anthony’s reps realize the problem: There is “delivery.com” branding all over the table. Almost in unison, they rush to block the picture: “Guys! Guys!”

The guys put down the cupcakes. Crisis averted.

* * *

Carmelo Anthony has never been a great sleeper. To this day, he’ll get five, maybe six, hours on a good night. But not long after the birth of his son, Kiyan, in 2007, Anthony wasn’t sleeping at all. The then-Denver Nugget had already established himself as one of the most dynamic offensive players in the game. What wasn’t yet clear was whether he would be able to translate his on-court dominance to off-court marketability — if he could, in other words, become the type of spokesman who needed expert guarding against renegade cupcake guys.

Though reputation had always been important to Anthony, who was born in Brooklyn and came of age in the same rough Baltimore neighborhood immortalized in The Wire, a 2005 profile in Esquire had made a point of saying how he “has struggled with becoming more brand than man,” while an article the next month in ESPN questioned if he could “ever be a first-tier pitchman.” It was a period of deep introspection, as Anthony tried to figure out how he could appeal to the suits as well as the streets, and if he even wanted to.

“You can’t change what you went through, how you grew up,” Anthony tells me, when we meet the next day at the Carnegie Club, a cigar lounge in Midtown. “I was almost my own victim my first few years in the league, because I didn’t want to let go of that. That was my identity.”

Anthony remembers hanging out with friends and going back to his old hood. He doesn’t get into specifics but shakes his head: “I can’t believe I was doing that.”

Publicly, there were drug charges (eventually dropped), complaints about Olympic playing time, a bar fight and an appearance on an underground DVD called Stop Snitching that discouraged individuals from cooperating with police investigations.

But that was the old Melo. As a new father, it came down to one word: reinvention.

“When I was trying to take my brand, my business, seriously, that was the one word I used to hang on the top of my board. Reinvention. How can I reinvent myself? It was hard, because I had to accept that I was becoming something else,” he says. “Being a man and being a brand at the same time … man, honestly, that took me a while. Sleepless nights.

“In order for you to get what you want, you have to let go sometimes,” Anthony continues. “I had to let go a lot.”

He has also gained a lot. In 2013, Anthony has associations with a growing list of businesses that include Jordan Brand, PowerCoco, Foot Locker, IWC, Isotonix, Haute Time and others. According to Forbes, he is the 25th highest-paid athlete in the world. And on the night before he delivered his best Gordon Gekko impersonation, Anthony made an appearance at the Bloomberg Sports Business Summit to talk about building a “billion-dollar brand.”

Not that there haven’t been flashbacks to the old Melo, as when he waited outside the Boston Celtics’ team bus after an on-court brush-up with Kevin Garnett in January 2013. Anthony insisted he wanted only to have a conversation, but he was suspended one game nevertheless after looking like a thug in the grainy security footage that played on “SportsCenter.” And as the CEO of Melo Enterprises knows, presentation matters.

Sitting in a stuffed leather chair on the mezzanine level of the Carnegie Club, Anthony swirls his glass of Macallan and smiles. “Ah, man. Reinvention is the best thing.”

* * *

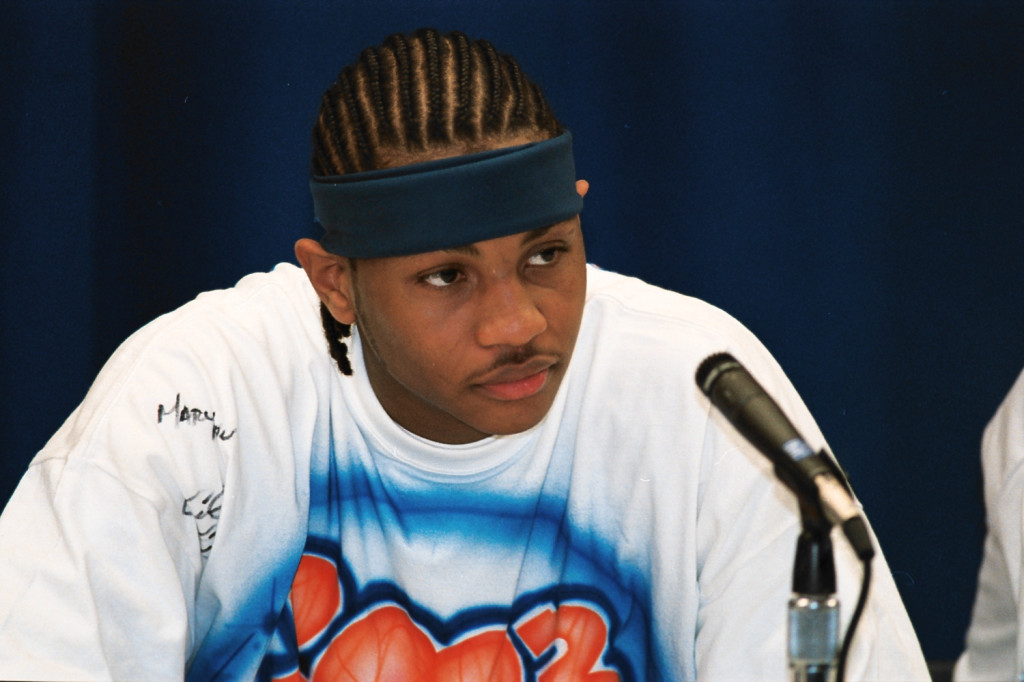

Carmelo Anthony of the New York Knicks after training at Madison Square Garden Training Center, in New York, Dec. 9, 2011. The team began their first day of training camp after an NBA lockout. (Todd Heisler | The New York Times)

To hear Anthony tell it, coming to the Knicks has always been part of a long-term plan. Upon arrival, he knew the depleted lineup, a result of the February 2011 deal that brought him to town, would take time to reassemble, and then there was the matter of adjusting to life in New York.

Given his background, Anthony believed he had thick enough skin to handle the city’s harsh win-now spotlight and sports tabloid culture. He was wrong.

“People in New York, they expect higher than they should expect, let’s just be quite frank,” Anthony says. “Which is good. That’s what makes New York New York. But it was like, OK, maybe I gotta put another layer [of skin] on.”

In his first half-season on Broadway, excitement returned to the Garden as Anthony teamed with fellow star Amar’e Stoudemire, before losing a first-round playoff matchup against the Celtics. In the lockout-shortened season that followed, Anthony still seemed to be in adjustment mode, suffering through injury and dealing with a coaching change (that many in the media suggested he helped orchestrate), while Linsanity swept New York on the shoulders of a clean-cut, Harvard-educated, ball-distributing guard named Jeremy Lin, who was basically Anthony’s polar opposite.

The ensuing criticism was withering: Maybe Anthony wasn’t as good as we all thought; maybe his sky-high potential is just that: potential, never to be realized. Anthony could have wilted under such scrutiny. But he was finally starting to understand the volatile rhythms of the city.

“My first year in New York, I had to go through some times, like, I really got to figure this out,” Anthony says, adding that he no longer watches highlight shows or reads the sports sections. “You have to approach life in New York day by day, because you’re only as good as yesterday. That’s what I figured out. By year three, which was last year, it was like, I got it now.”

He got it, all right. Anthony had his most productive year as a pro in 2012-13. In addition to the scoring title, he shot a career best from three-point range and notched his highest-ever PER (an advanced-metric stat that stands for “player efficiency rating”), which also saw him lead James Dolan’s long-suffering and oft-dysfunctional basketball franchise to its first division title in nearly two decades and its first postseason series win since 2000. The Garden faithful rewarded Anthony with frequent “M-V-P” chants, and he was be the only player other than eventual winner LeBron James to receive a first-place vote.

Knicks legend and MSG Network commentator Walt “Clyde” Frazier noticed the difference in Anthony immediately. “He realized he’s the man, and if it’s going to get done, he has to do it,” Frazier says. “There was a lot of pressure on him to deliver. And he did.”

Even when the season ended in disappointment, thanks to a manhandling by the Indiana Pacers in round two, it was widely understood that the Knicks superstar wasn’t to blame. And so what if the lasting image of that series was Anthony getting rejected at the rim by Roy Hibbert? He had firmly shifted the conversation: No longer does anyone debate whether he belongs in the city; now it’s a matter of whether he’ll stay.

* * *

There’s no question that the Nets, not the Knicks, owned the back pages in the summer. Hiring Kidd was a splashy move, and that was only the beginning, as the team added future Hall of Famers Paul Pierce and Kevin Garnett in a blockbuster trade with the Celtics.

“When you hit a home run, you become the face of the off-season,” Anthony says, dismissing the idea that any lingering tension with Garnett will add intrigue to the intra-city matchup. “I think what they were able to do really took them to another level, a contender level.”

Pierce, a perennial thorn in the Knicks’ side, chirped about how “it’s time for the Nets to start running this city,” while Knicks guard Raymond Felton insisted that will never happen. Anthony has said he believes the teams will develop the “best rivalry in basketball” but prefers to abstain from the back-and-forth. On one hand, he understands that, if he were still that kid growing up in Brooklyn, he would have to root for the Nets. “That’s the new hype, that’s fresh, so you gotta root for that,” he says. On the other hand, he believes, “this will always be a New York Knicks town.”

All this chatter is just foreplay for the summer of 2014, when the headlines will belong to Anthony, as he decides whether to opt out of his contract. In what promises to be the greatest free-agent class in NBA history, he’s poised to make more money than anyone, including James. He’s also poised to endure more criticism. Despite his banner year, player evaluators still describe Anthony as “not good enough to be the best player on a legitimate title contender” and not having “shown the ability (or desire) to elevate the other parts of his game necessary to take a good team to greatness.”

Often cast in the role of Anthony’s biggest fan, Jim Boeheim has enjoyed a courtside seat for the evolution of Carmelo Anthony, first as his head coach at Syracuse University, where together they won an NCAA title, and then as an assistant with recent Olympic and FIBA teams. “Carmelo is a scorer,” Boeheim explains. “So people tend to criticize scorers more than they would passers. You know, why doesn’t he pass more? But that’s not what he does. He’s a scorer. For New York to win, everybody has to play well.”

(That was not the case versus Indiana.)

Anthony is clear he expects to win a title. “I feel like I’m going to get one, this year, next year. I still got a long time in this league,” he says. But even if he doesn’t, Anthony rejects the semantics that one has to win to be a winner. “Barkley, Ewing, John Stockton, Karl Malone, Reggie Miller — you mean to tell me they’re not great? Yeah, a championship validates that. But these guys are great.”

That attitude might prove good news for the home team, since the Knicks will finish in the lower half of playoff qualifiers in the now-stacked Eastern Conference. The team has a losing record, but it’s right at the No. 8 playoff position. As Howard Beck wrote in The New York Times, Anthony’s decision in the summer might come down to staying in New York versus winning elsewhere.

“I want to be a free agent,” Anthony tells me, as our cigars burn close to the nub. “I think everybody in the NBA dreams to be a free agent at least one time in their career. It’s like you have an evaluation period, you know. It’s like if I’m in the gym and I have all the coaches, all the owners, all the GMs come into the gym and just evaluate everything I do. So yes, I want that experience.”

Take a breath, Knicks fans. That doesn’t mean he’s leaving.

“I came to New York for a reason,” Anthony adds. “I’ve been with you all my life, almost to a fault. I wanted to come here and take on the pressures of playing in New York. So one thing I would tell my fans: If you haven’t heard it from me, then it ain’t true.”

* * *

Like many modern hoops stars, Anthony talks openly about balancing “the game of basketball and the business of basketball,” which fans understandably hear as athlete-speak for “no promises.” Still, it’s hard to imagine him leaving the city. His family is settling into a new place on the Upper East Side, and his son has just started the first grade. In fact, Anthony has come to the cigar lounge straight from a parent-teacher conference.

With his custom conversion van waiting outside, Anthony stretches out his legs and seems to enjoy the relative peace of the mezzanine, even with the tape recorder whirring. “I feel like I’m a people’s person,” he says. “But sometimes I just want to find spots like this, low-key spots, and chill out and relax.”

Or hang with his family. According to Anthony’s wife, La La, a celebrity in her own right, finding private time is a priority for the public couple. “The public can’t get inside our house, but we like to do a lot of things,” she says. “We like to go to the movies. We might go five minutes after it starts and sneak in the back row, but you find ways.”

Without a Wall Street stop on today’s agenda, Anthony is dressed casually, in jeans and a military-inspired button-up (camo is one of his sartorial staples). I wonder if the 6-foot-8 superstar is ever really able to blend in, though, darkened theaters notwithstanding.

“No! Hell no,” he laughs.

Which reminds me: Have you heard the one about the Hasid and the elevator?

Carmelo Anthony and a Hasidic Jew walk into an elevator. The Knicks franchise player stands against the back wall, while the Hasid, long side curls tucked neatly behind his ears, waits until the doors close before turning to face the athlete.

“Bring us home a ring,” the Hasid says. “We need one.”

Anthony replies, “We all need one.”

As the elevator continues to climb, the Hasid looks away but mutters, “A long time we’ve been waiting.”

Anthony forces a smile. This is not a joke.

This story originally appeared in the New York Observer.

For more Syracuse New Times COVER STORIES – CLICK HERE

[fbcomments url="" width="100%" count="on"]