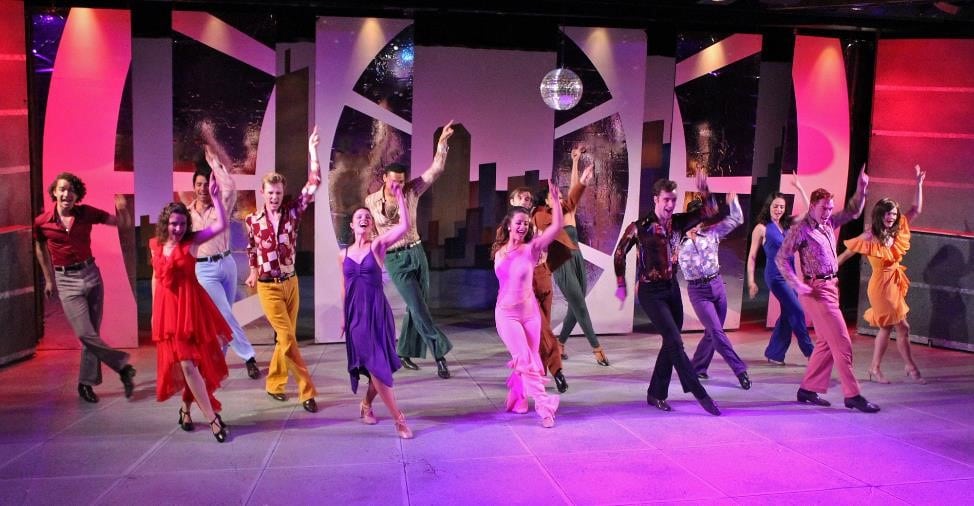

Happy feet ignite Cortland Repertory’s funky flashback ‘Saturday Night Fever’

Disco died, but Saturday Night Fever still lives. It’s a paradox: Although a fashion moment, with bell-bottom pants and bright colors, fades away, one of its prime expressions, a 41-year-old movie, has not become campy and is still in many people’s minds.

Director John Badham’s 1977 film never has to be revived, because it never went away. What is surprising is that the stage version, a compelling crowd-pleaser, is seen so little. Cortland Repertory Theatre brings us up to speed on that, with a splashy show running through July 7.

Producer Robert Stigwood brought Fever to the London stage in 1998, where its success prompted a 501-performance run in New York City during 1999 and 2000. Although two committees of writers worked on both the London and New York versions, the Cortland production is generally faithful to the movie, whose script is notably anti-romantic. Hearing those pounding feet on stage, we get 42nd Street with grit. For all the betrayal and disappointment, it’s the music that transports us.

They should be dancing: Michael Russell and Emily Janes in Saturday Night Fever. (Provided by Kerby Thompson)

Producing artistic director Kerby Thompson takes charge of the entire production with skillful maximizing of the intimate space of the Little York Pavilion. That means light, stylized, quickly mobile sets by Darin Himmerich.

Thompson also underscores all the nondance drama, such as Tony’s bickering patriarchal family, his spoiled priest brother Frank Jr. (Kyle Kniseley), failed relationships, gang violence, and racial discrimination against Puerto Ricans. Yet Thompson gains tremendously in bringing in two newcomers to Cortland.

New York-based music director Shoshana Seid-Green appears to be too young to have known the disco-era heyday of the Bee Gees but she knows it from the inside. Leading an orchestra of eight, she digs into the vibrancy of the score without betraying its fundamental lyricism. Disco was always about dance. As with so much of the show, she treats the music as if it were brand new rather than a kind of nostalgia.

Then again, Seid-Green does not have the voices to duplicate the Bee Gees’ distinctive falsetto. Yet she slips in some bluesy motifs in laments for lost love, like Annette’s “If I Can’t Have You,” performed by Stephanie Garofalo.

An even bigger find is choreographer Bryan Knowlton, with extensive Broadway and national credits, along with multiple awards and nominations. The full ensemble is in motion in nine production numbers, and the male quartet — called the “Faces,” with Bobby (Christian Henry), Joey (John Cavaseno), Gus (Braden Phillips) and Double J (Jahmar R. Ortiz) — scampers through two more.

As with the music, Knowlton’s choreography evokes and recreates rather than mimics. Still, when Tony Manero (Michael Russell) steps out in the iconic white suit, there’s an audible gasp from the audience.

John Travolta was 23 and at the peak of his tough-tender charm when the movie came out, a difficult paradigm for any actor to fill. Michael Russell has the fine features of a Florentine prince rather than a rowdy from Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge, but he speaks the language of the streets. His Tony is flippant in dealing with his gruff employer, Mr. Fusco (Doug Walls), at the paint store, but he still has to be a kid at dinner with his squabbling family.

Musically, Russell is a vastly superior singer to Travolta, starting out with “Stayin’ Alive,” and more than matches him on the dance floor. His biggest number is arguably “After the Fall,” just before the finale.

Emily Janes as the well-born and ambitious Stephanie Mangano defines her role more easily. Many audiences have forgotten the name of Karen Gorney (then nine years older than Travolta) in the film, but she seemed superior and inaccessible. Janes has the voice, the hoofs and the manner. Her solo, “What Kind of Fool,” resonates with the deepest feeling.

Of the many things that make Saturday Night Fever a better show than remembered is its rootedness. Tony’s need for dance, and therefore his hunger for artistic expression, comes from his claustrophobia in being locked in dead-end labor and the bitter gruel of his home life.

Director Thompson pulls no punches in portraying a hideous dinner at the Manero household. His impotent bully of a father, Frank Sr. (Jimmy Johansmeyer, who is also the show’s witty costumer), is between jobs, and rages when his wife, Flo (Jan Labellarte), suggests she might bring in an extra wage. Frank Sr. also stops Tony from cleaning up the table with “Let the girls do it.” These are not Italian-American Kramdens but rather soul-killers.

As is widely known, the stimulus for the original script of Saturday Night Fever was a 1976 article by British émigré journalist Nik Cohn titled “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night” in New York magazine. Less well-known is that two decades later Cohn confessed that he was befuddled by the assignment to cover the Bay Ridge dance scene, so he based the character of Tony on an Englis working-class “mod” that he knew in the 1960s. Well, as Elie Wiesel once said, “Some stories are true that never happened.”

[fbcomments url="" width="100%" count="on"]